When people begin to understand how much electricity a modern country actually needs, a natural idea often follows:

“If we sometimes produce more electricity than we use, why not store the excess and use it later?”

At first glance, this sounds reasonable. Storage works well in everyday life. We store water, fuel, food, and data. Surely electricity can be treated the same way.

This article takes that intuition seriously—and then examines what happens when energy storage is expected to work at national scale, for days or weeks, rather than minutes or hours. The goal is not to dismiss energy storage, but to show, with concrete numbers, where its limits appear.

To keep the discussion grounded, we use Sweden as an example.

Population: ~10.5 million

Annual electricity use (typical range): 130–145 TWh

Average electricity use per week: ≈ 2.6 TWh

That equals:

2.6 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh)

Any storage method discussed below must be understood in relation to this number.

Energy storage does not generate electricity.

It only moves electricity from one moment to another.

That always involves:

physical infrastructure

conversion losses

space and materials

cost per unit stored

At small scales, these drawbacks are manageable. At national scale, they compound rapidly.

Most storage technologies work well for:

seconds (grid stability)

minutes (frequency control)

hours (daily balancing)

Very few work cleanly for:

multiple days

entire weeks

A system designed to cover one hour must be multiplied by 168 to cover one week. At that point, scale becomes the dominant constraint.

Hydrogen is often proposed as a solution for long-term storage because it can, in principle, be stored for long periods.

To keep the example fair, we intentionally use optimistic assumptions that favor hydrogen.

Electricity to hydrogen: ≈ 50 kWh of electricity to produce 1 kg of hydrogen

Hydrogen back to electricity: ≈ 20 kWh of electricity per kg of hydrogen

Storage pressure: 350 bar (professional compressed-gas storage)

These assumptions already ignore compression losses, transport losses, and downtime.

Sweden’s weekly electricity use:

≈ 2.6 billion kWh

At 20 kWh per kg of hydrogen, the required hydrogen mass becomes:

≈ 131 million kilograms of hydrogen

≈ 131,000 tonnes

How much space does that hydrogen occupy?

How much space does that hydrogen occupy?At 350 bar, compressed hydrogen has a density of about 23–24 kg per cubic meter.

That means:

≈ 5.5 million cubic meters of compressed hydrogen gas

To make this relatable:

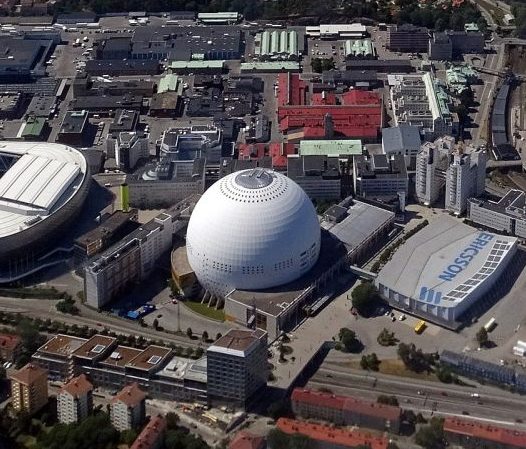

Avicii Arena in Stockholm has a volume of roughly 605,000 cubic meters

≈ 9 Avicii Arenas, filled to the rim with 350-bar pressurized hydrogen, would be needed to supply Sweden with electricity for just one week

This figure refers only to the gas volume—not storage tanks, structural material, safety distances, compressors, or backup capacity.

Hydrogen can be useful for:

industrial processes

chemical feedstock

certain transport applications

absorbing occasional surplus energy

What these numbers show is that hydrogen struggles as a method for national-scale electricity backup, not because it is useless, but because volume and infrastructure requirements grow too large too quickly.

Batteries are excellent at what they are designed for:

very fast response

high round-trip efficiency

short-duration grid support

Their challenge at national scale is not volume, but mass and materials.

To remain fair, we again choose optimistic values.

A realistic but generous system-level energy density for large grid batteries is:

≈ 200 Wh per kg

(0.2 kWh per kg, including packaging, cooling, and control systems)

Sweden’s weekly electricity use:

2.6 billion kWh

At 0.2 kWh per kg, the required battery mass becomes:

≈ 13 billion kilograms

≈ 13 million tonnes of batteries

This does not include:

buildings and foundations

inverters and transformers

cooling and fire protection

spare capacity or redundancy

Large batteries degrade over time, even when lightly used.

A generous planning lifetime is:

10–15 years

That means a national battery backup system would require continuous replacement of millions of tonnes of batteries every decade, turning storage into a permanent industrial production effort rather than a one-time investment.

Pumped hydro is the most mature form of large-scale energy storage.

It works by:

pumping water uphill when electricity is abundant

releasing it through turbines when electricity is needed

However, storing weeks of national electricity would require:

enormous water volumes

large elevation differences

vast land areas

Suitable locations are rare, often environmentally sensitive, and already largely used where available.

Even in favorable countries, pumped hydro supports balancing, not full national backup.

At national scale, terms like “large” or “significant” lose meaning.

The relevant descriptors become:

billions of kilowatt-hours

millions of cubic meters

tens of millions of tonnes

infrastructure measured in city-sized dimensions

At this point, storage is no longer a supporting technology. It becomes a second energy system, with its own environmental, material, and economic footprint.

Energy storage plays a valuable role when used appropriately.

It excels at:

smoothing short-term fluctuations

stabilizing grids with variable generation

reducing peak demand

improving efficiency of existing systems

What it does not do well is replace reliable, continuous electricity generation for extended periods.

At national scale, energy storage is best understood as a supporting tool, not a foundation.

For a country like Sweden:

storage can improve stability

storage can reduce waste

storage can help manage variability

But even under generous assumptions, storage alone cannot realistically power society for days or weeks when generation is constrained.

Understanding this does not mean rejecting storage.

It means using it where it works, and not expecting it to solve problems that physics does not allow it to solve.

This is an article series "Energy Reality" containing: