Long before gingerbread meant warm kitchens, icing, and children breaking off corners of houses, it was something rarer—and taken far more seriously.

Its story begins not with Christmas, but with distance.

In medieval Europe, ginger was not a flavor you stumbled across. It came by ship and caravan from Southeast Asia, passing through countless hands before reaching northern markets. Every step added cost. By the time it arrived, ginger was a spice for the wealthy, the sick, or the devout.

It was valued not just for taste, but for reputation. Ginger was believed to warm the body, aid digestion, and restore balance. In an age where food and medicine overlapped, spices were closer to remedies than indulgences.

Honey, another essential ingredient, was also precious. Sugar existed, but it was rarer still—an imported luxury used sparingly, often kept under lock. Flour was common, but alone it was not enough to justify baking something special.

Gingerbread, in its earliest form, was therefore not everyday food. It was ceremonial.

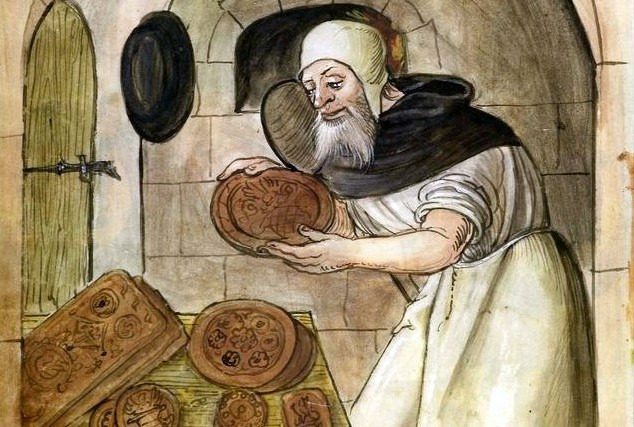

Some of the earliest European gingerbread was produced in monasteries. Monks had access to spices through trade networks and donations, and they worked with precise rules about fasting, feasts, and moderation.

The “bread” itself was often dense and dark. Sometimes baked, sometimes pressed into molds. Sometimes not baked at all, but set and dried. The shapes mattered: saints, symbols, coats of arms. Gingerbread was something you looked at before you ate it.

It was given on special days. Pilgrimages. Church festivals. Important visits. A small piece carried meaning because the ingredients themselves were uncommon.

Availability was limited not by demand, but by logistics.

As centuries passed, trade improved. Spice routes stabilized. Ginger became less rare—not cheap, but reachable. Honey remained central, but sugar slowly entered kitchens as colonial production expanded.

With availability came experimentation.

Bakers outside monasteries began to work ginger into festive breads and cakes. Towns developed reputations for their gingerbread. Certain recipes became local secrets. Molds became more elaborate, turning gingerbread into something decorative as well as edible.

It was still not everyday food. But it had shifted—from medicine to celebration.

The link between gingerbread and Christmas was not inevitable. It emerged gradually, shaped by season and necessity.

Winter was when:

preserved ingredients were relied upon

spices helped mask staleness

baking became communal, done in batches

Ginger, with its warming reputation, fit winter well. Honey and sugar preserved baked goods longer. Dense breads kept.

Christmas, meanwhile, was one of the few times of year when indulgence was not only allowed, but expected. Rich foods appeared briefly, then vanished again. Gingerbread belonged to that window.

It became associated with the exception, not the rule.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, gingerbread had crossed an important threshold: it became predictable.

Ingredients were still valued, but no longer extraordinary. Families could expect to bake it every year. Recipes were passed down. Shapes became playful—hearts, animals, later houses.

What had once been rare enough to symbolize wealth or devotion now symbolized tradition.

That shift mattered.

A food does not become festive because it is luxurious. It becomes festive because it is reserved. Gingerbread’s power lay in its restraint—made once a year, associated with cold air, candlelight, and time set aside from ordinary work.

Despite the transformation, something endured.

Gingerbread has always been:

spiced more than necessary

sweet beyond hunger

made to be shared

It was never efficient food. It was never practical. Even today, gingerbread houses are built knowing they will collapse, be eaten unevenly, or thrown away.

That, too, is part of the point.

Gingerbread began as something rare because its ingredients came from far away. It remains special because it is still, deliberately, out of place—a sweet interruption in the year.