Across many democracies, people increasingly feel that political labels no longer match reality. Positions that were once considered mainstream are now described as “right-wing,” while views previously labeled progressive are treated as centrist. This perception is not simply partisan frustration—it reflects a real and well-documented phenomenon in political analysis: the movement of reference points over time.

Understanding this requires separating policy change from label change.

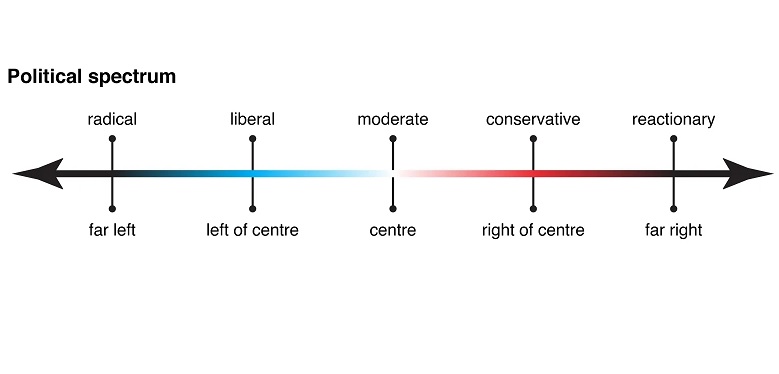

Terms like left, center, and right do not represent permanent coordinates. They are relative positions within a moving landscape. As dominant ideas, institutions, and priorities evolve, the meaning of these labels shifts with them.

What counts as “center” is always defined by:

prevailing social norms

dominant policy frameworks

institutional consensus

media and academic language

When these shift, the labels shift—even if individuals do not.

Over the past several decades, many Western societies have seen sustained movement toward:

expanded government involvement in social and economic life

broader definitions of rights and state responsibility

stronger regulatory frameworks

moral framing of political disagreement

None of these trends are inherently good or bad by definition. The key point is that they reset the baseline.

Policies that once represented the left edge gradually became normal, then institutionalized. Once that happens, the center relocates—not because people voted for “the left,” but because yesterday’s left became today’s default.

As the center shifts leftward:

Positions that haven’t changed appear to move right

Moderates are reclassified as conservatives

Skepticism is framed as opposition

Dissent is increasingly moralized

This creates the impression that “the right” is growing more extreme, when in many cases the reference point has simply moved past them.

A person standing still appears to move backward when the platform beneath them advances.

In a polarized environment, language compresses nuance.

When the political spectrum narrows around a new center:

views outside that range are grouped together

distinctions between conservative, classical liberal, and nationalist positions blur

criticism of dominant narratives is treated as ideological opposition

As a result, the term right-wing extremist is sometimes applied less as a precise descriptor and more as a boundary marker—signaling that a view lies outside accepted discourse.

This does not mean real extremism does not exist. It does mean that the category has expanded, while the space for legitimate disagreement has narrowed.

Institutions tend to stabilize around existing power structures. Over time, shared assumptions develop about:

which views are “reasonable”

which questions are “settled”

which positions are “dangerous”

Media organizations, academic environments, and bureaucratic systems often reflect these assumptions—not through coordination, but through shared incentives and cultural alignment.

This creates feedback loops:

dominant views receive more validation

alternative views receive more scrutiny

labels replace arguments

Again, this is not necessarily intentional. It is structural.

When large segments of the population feel that:

their views are mischaracterized

disagreement is treated as moral failure

labels are applied without precision

trust erodes.

People do not disengage because they reject democracy. They disengage because they feel misunderstood, dismissed, or pre-judged.

Healthy political systems require:

room for disagreement

stable definitions

tolerance for nonconformity

and clear distinctions between disagreement and extremism

Without those, polarization accelerates.

Rather than asking:

“Why has the right become more extreme?”

A more accurate question is often:

“How has the definition of the center changed?”

That reframing:

reduces hostility

restores context

allows for disagreement without demonization

Political change is inevitable. But when language stops describing reality accurately, it stops being useful.

The perception that “everything has moved left” is less about conspiracy and more about gradual baseline change. As policies, norms, and institutions evolve, yesterday’s center becomes today’s right—and today’s left moves further outward.

Understanding this does not require choosing sides.

It requires recognizing that political language is dynamic, and that mislabeling disagreement as extremism weakens democratic conversation rather than protecting it.

A stable society depends not on enforced consensus, but on clear definitions, proportional language, and space for honest disagreement.

That is not a left or right position.

It is a democratic one.